STANBUL (Reuters Life!) – Along Istanbul's busy Eminonu waterfront women swathed in dark coats and scarves knotted once under the chin jostle past others clad in vivid colors and head coverings carefully sculpted around the face.

Two decades ago such a polished, pious look scarcely existed in Turkey. But today it has the highest profile exponents in First Lady Hayrunnisa Gul and Prime Minister Tayyip Erdogan's wife Emine, and the brands behind it plan ambitious expansion.

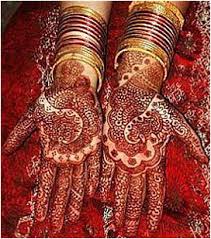

The headscarf remains one of Turkey's most divisive issues. Everything from the way it is tied and accessorized, to the poise and demeanor of the wearer, is laden with meaning in this majority Muslim but officially secular country of 74 million.

From a simple headcovering, stigmatized in the early days of the Turkish Republic as backward and rural, it has become, in the last decades, a carefully crafted garment and highly marketable commodity, embodying the challenge of a new class of conservative Muslims to Turkey's secularist elites.

"It was hard to find anything chic for the covered women 10 years ago, but fashion for pious women has made huge progress in the last 6-7 years," said Alpaslan Akman, an executive in charge of production and marketing at Muslim fashion brand Armine.

Armine is known for its high-impact campaigns. Huge posters have hung in the heart of Istanbul's bar and nightclub district -- the serene models contrasting with the commotion below.

The brand teams colorful scarves with figure-skimming coats, pert collars, big buttons and ruffled sleeves.

A coat typically sells for around 200 Turkish lira ($143.2), while scarves retail for around 50 lira.

"We are much luckier than previous generations, we have more designs and colors of scarves to choose from," said 30-year-old Filiz Albayrak, a sales assistant in an Istanbul scarf shop.

Around 69 percent of Turkish women cover their heads in some form, with 16 percent using the more concealing and self-consciously stylish "turban" style scarf, which tightly covers the hair and neck, according to a 2007 study.

Getting it to sit right takes much time and effort, and usually requires an under bonnet to first provide a stiff base.

GROWING CONFIDENCE

Turkey's first lady, who wears a turban, co-hosted Republic Day celebrations with her husband for the first time last month, in a sign of confidence among the pious establishment.

Encountering Hayrunissa Gul in her headscarf in the Presidential Palace was too much for the staunchly secularist military however, who refused to show up.

Mustafa Karaduman, founder of Islamic fashion house Tekbir in 1982 and nicknamed "Allah's Tailor" in the Turkish media, sees the changes in society and is hopeful of further growth.

"Our work was quite amateur in the first decade. Then in 1992 we organized the very first headscarf fashion show, which brought us global attention. Now Islamic style clothes are on the agenda everywhere around the world," he said.

He plans to add to his 90 stores in Turkey and 10 abroad. Armine, like Tekbir also has ambitious expansion plans.

"We are very aggressive in terms of targets...I'll say we are successful when the day comes that people think 'Who's Armani? It must be fake Armine,'" joked Akman.

Turkish daily Milliyet estimated the Islamic clothing market to be worth $2.9 billion.

Despite its presence on the streets, women students and civil servants are banned from wearing the scarf in the institutions of the secular state, a rule the governing AK Party, led by conservative Muslims, has pledged to end.

The secular establishment fears any change to the ban could see uncovered women feel pressure to cover their heads.

An attempt by the AK Party to remove the ban three years ago was blocked by the Constitutional Court and nearly saw the party closed down for anti-secular activities.

Continued discussions over the headscarf mirror Turkey's socio-economic development and the struggle over the defining line between the country's political and religious characters.

Rapid economic growth has given many people more income to spend on themselves, while rising political consciousness among an ascendant class of pious Muslims has led to highly visible veiling as they stake a claim in society.

Religion became more prominent in society after a 1980 military coup, and was tolerated as a foil to leftist ideologies. Young urban women started wearing home-made baggy coats and large scarves as a political statement, according to Ozlem Sandikci, assistant professor of marketing at Ankara's Bilkent university.

Garments gradually became more shapely and colorful, as pious women wanted to be seen and acknowledged, she said.

"Turkey already had the textile know-how. So as women started to cover it is obvious that business would emerge and start to supply them. These small companies began to grow and have become increasingly influential players," she said.

Today the most conservative Muslims frown on the Islamic fashion industry's commodification of the headscarf, while staunch secularists say the clothes are ostentatious and betray little of the modesty that wearing a headscarf is supposed to express.

"Modesty is a requirement but it is not the only requirement," Sandikci said. "Women are also supposed to demonstrate a pleasant look so as to act as a role model, and a positive example of Islam."

(Additional reporting by Ece Toksabay; Editing by Paul Casciato)